Ⅰ. 서 론

최근 노인 인구가 급증함에 따라 노화로 인하여 기억력 (memory), 주의집중력(attention), 실행 기능(executive function), 정보처리속도 등에 어려움을 보이는 노인이 증가하고 있다(Glisky, 2007). 인지 손상으로 인해 기능 적 독립성이 저하되고 사회적 참여가 줄어들어 삶의 질 에 악영향을 미친다(Ertel, Glymour, & Berkman, 2008; Gaugler, Duval, Anderson, & Kane, 2007). 관 찰연구 결과, 기억력 손상이 있거나 인지 손상을 보이는 노인은 시간이 지남에 따라 알츠하이머 치매에 걸릴 가 능성이 증가하는 것으로 나타났다. 그러므로 노인의 인 지 기능 저하를 지연 시키는 것은 알츠하이머 치매 예방 에 매우 중요할 것으로 보인다(Van Oijen, De Jong, Hofman, Koudstaal, & Breteler, 2007).

노화로 인한 저하된 인지 기능을 향상 및 유지시키기 위해 여러 가지 비약물학적 접근들이 연구되어 왔다. 전 략 훈련, 처리 훈련, 행동 기반 접근법, 심혈관 훈련, 다중 적 접근법 등 다양한 유형의 비약물적 인지 훈련은 정상 인지노인과 인지 손상 노인에게 인지 및 수행 기능 측면 에서 긍정적 효과가 검증되어 왔다(Lustig, Shah, Seidler, & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009). 이 중 상당수의 인 지 훈련 프로그램들은 훈련된 치료사에 의해 개인 혹은 그룹의 형태로 직접 대면(face-to-face)하여 지필 (paper and pencil) 방식으로 시행되었다. 대면 방식의 훈련은 자택에서만 생활하거나, 요양 및 보호시설에 거 주하거나, 교통 접근성에 이용이 불편한 노인들과 접촉 하기 어렵기 때문에 치료 장소, 일정, 이동 시간 등에 대 한 제한점이 많다(Wadley et al., 2006).

현대 과학 기술의 발달과 함께 노인을 대상으로 컴퓨 터를 이용한 새로운 형태의 전산화 인지 훈련 방법이 개 발되고 있다. 전산화 인지 훈련의 장점은 실시간으로 수 행에 대한 피드백이 가능하고 기억력, 주의집중력, 반응 속도 등의 영역별 수행도에 따라 난이도를 조절할 수 있 기 때문에 대상자의 능력에 맞게 도전적인 과제 훈련을 제공할 수 있다(Clare, Woods, Moniz Cook, Orrell, & Spector, 2003). 특히, 게임 형태의 프로그램은 흥미 요 소를 더하여 동기 부여가 가능하다(Kueider, Parisi, Gross, & Rebok, 2012). 또한 직접 대면 방식에 비해 시각적인 인터페이스를 제공하여 접근성을 높일 수 있고 비용-효과적이며 중재를 받기 어려운 지역사회 거주자 들에게도 쉽게 보급할 수 있다(Jak, Seelye, & Jurick, 2013).

선행연구들을 살펴보면 정상 노인, 경도인지장애, 뇌 졸중 등을 대상으로 전산화 인지 훈련을 실시한 실험연 구들은 많이 있었지만, 그 효과에 대해서는 일치된 결과 를 보이지 않았다(Lampit, Hallock, & Valenzuela, 2014; Reijnders, van Heugten, & van Boxtel, 2013). 기존에 수행된 고찰 연구에서는 특정 질환을 가진 노인 으로 국한되어 있었고, 비무작위 임상실험설계 연구와 단일대상연구 등 다양한 실험설계 연구를 포함하고 있었 다(Cha & Kim, 2012; Kueider, Parisi, Gross, & Rebok, 2012). 그러므로 Arbesman, Scheer와 Liverman (2008)의 질적 근거 수준 분석모델에서 1단 계에 해당하는 무작위 임상실험설계 연구(Randomized Controlled Trial; RCT)의 체계적 고찰을 통해 전반적 인 노인에 대한 그 효과를 검토할 필요성이 있다.

따라서 본 연구의 목적은 최근 10년 동안의 무작위 임 상실험설계 연구를 고찰하여 노인의 인지 기능을 향상시 키기 위한 전산화 인지 훈련이 어떠한 효과가 있는지를 알아보고자 하는 데에 있다. 이는 전산화 인지 훈련의 최 근 동향을 제공하여 노인을 대상으로 전산화 인지 훈련 을 적용하는 임상현장의 작업치료사에게 기초자료를 제 시하고자 한다.

Ⅱ. 연구 방법

1. 논문 검색 및 데이터 수집

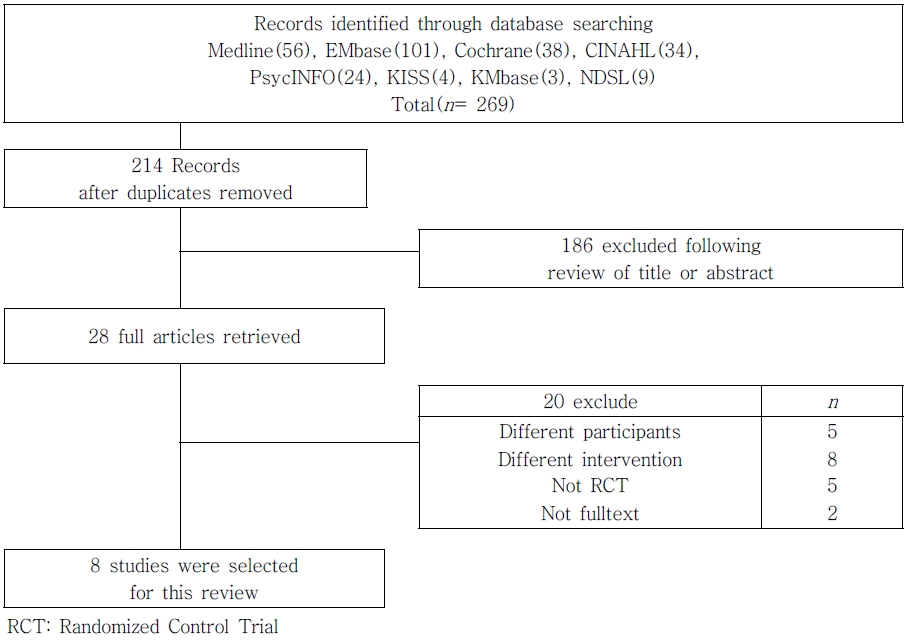

본 연구는 노인에 대해 전산화 인지 훈련 중재를 실시한 연구들을 검토하기 위하여 웹 데이터베이스를 통해 2006 년부터 2016년까지의 국내외 학회지 문헌들을 수집하였 다. 2016년 3~5월에 걸쳐 Medline, EMbase, Cochrane, CINAHL, PsycINFO, KISS, KMbase, NDSL 데이터베이 스에서 ‘Therapy, Computer-Assisted (Mesh term)’, ‘Aged (Mesh term)’, ‘Cognitive Therapy (Mesh term)’, ‘Randomized Controlled Trial (Publication Type)’, ‘노인’, ‘전산화 인지’를 키워드로 검색하였다. 논 문 유형은 무작위 임상실험설계 연구로 제한하였으며, 제1 저자와 제2저자가 검색된 연구에 대해 제목과 초록을 검토 한 후 필요시 원문을 확인하였다. 두 명의 연구자가 다른 의견이 있을 경우 모든 저자가 함께 토의를 하여 결정하였 다. 이에 따라 포함기준과 배제기준에 의거한 본 연구의 분석 대상은 최종적으로 8개가 선정되었다(Figure 1).

2. 방법론의 질적 평가

최종적으로 선정된 8편의 연구에 대하여 두 명의 연구 자가 방법론의 질적 평가를 수행하였다. 질적 평가를 위 해서는 무작위 임상실험설계 연구의 방법론적 질을 평가 하기 위해 개발된 PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) scale을 적용하였다(Bhogal, Teasell, Foley, & Speechley, 2005). PEDro scale은 10개의 각 항목 에 대해 1점씩 배점하여 0~10점의 범위를 가지며 (Table 1), 총점 9점 이상은 ‘아주 좋음’, 6~8점은 ‘좋 음’, 4~5점은 ‘보통’, 3점 이하는 ‘나쁨’으로 분류한다 (Moseley, Herbert, Sherrington, & Maher, 2002).

Table 1

Operationalization of Validity Criteria

3. 연구 분석

각각의 연구에 대해 연구 참가자 그룹의 유형 빈도와 인지 영역별로 기억력, 주의집중력, 실행 기능, 전반적 인지 기능(global cognitive function), 기타 등으로 구분하여 이에 대한 종속변수의 빈도수를 분석하였다. 또한 전체 연구들을 체계적으로 정리하기 위하여 저자/연도, PEDro score, 집단별 연구 대상자, 집단별 중재 유형, 집단별 중재 강도, 종속변인, 평가도구, 결과 순으로 나열하였다 (Table 4).

Ⅲ. 연구 결과

1. 방법론의 질적 평가

본 연구의 분석 대상 논문에 대한 방법론의 질적 수준 을 PEDro 척도에 따라 분석한 결과, 8점이 25.0%(2 편), 7점이 37.5%(3편), 6점이 37.5%(3편)를 차지하 였으며 평균 6.9점으로 나타났다. 방법론의 질적 수준은 대상 논문 전체가 6~8점인 ‘좋음’범주에 속하였다. 각 점 수는 Table 5에 제시하였다.

2. 전산화 인지 훈련 중재

1) 연구 참가자 유형

인지 향상을 위한 전산화 인지 훈련 중재 연구에 참여한 노인 참가자의 유형은 경도인지손상 환자가 45.5%, 정상 노인이 27.3%을 차지하였다. 그 다음으로는 알츠하이머 병이 18.2%, 뇌졸중이 9.1%의 비율을 차지하였다(Table 2). 정상 노인을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 그 선정기준을 간이정신상태검사(Mini Mental State Examination; MMSE) 점수가 24점 혹은 26점 이상인 자로 하였다. 참가 자 그룹의 유형이 중복되는 논문에 대하여, 먼저 Gaitan 등(2013)은 대상자를 경도인자손상 환자와 초기 알츠하 이머병으로 함께 선정하였고, Barban 등(2016)은 경도 인지손상, 알츠하이머병, 정상 노인 각각에 대하여 무작위 임상실험 설계 연구를 하였기 때문이다.

2) 측정된 종속변인

전산화 인지 훈련 중재의 효과 검증을 위해 측정한 종 속변인을 기억력, 주의집중력, 실행 기능, 전반적 인지 기 능, 기타 등의 인지 영역별로 분류하고 그 빈도수를 분석 하였다. 그 결과 기억력이 31.6%이고, 전반적 인지 기능 은 21.0%, 실행 기능, 주의집중력, 기타는 각각 15.8% 를 차지하였다. 나머지 기타 종속변인은 15.8%를 차지 하였으며 언어적 유창성, 우울척도, 자기효능감, 수단적 일상생활활동 등을 포함하였다(Table 3).

3) 참가자 유형별 효과 분석

(1) 알츠하이머병

치매 노인을 대상으로 한 두 편의 논문은 모두 경도 알츠하이머병을 대상으로 하였다. Barban 등(2015)의 연구에서는 회상치료를 적용한 그룹보다 전산화 인지 훈 련을 실시한 그룹이 기억력과 전반적 인지 기능이 유의 하게 향상되었고, 중재기간 중에는 수단적 일상생활활동 (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; IADL)의 기 능적 수준이 유의한 향상을 보였다. Gaitan 등(2013)의 논문에서는 실험군에게 전산화 인지 훈련과 전통적 인지 훈련을 각각 30분씩 적용하였으며 대조군은 전통적 인 지 훈련만 60분씩 실시하였다. 그 결과, 불안(anxiety) 과 의사 결정(decision making)에서만 유의한 향상을 보였을 뿐, 인지 기능에서는 유의한 효과를 보이지 않았 다. 하지만 모든 인지 관련 종속변수에서 실험군이 대조 군보다 긍정적인 효과 크기를 보였으며 12개월 후의 추 적평가에서는 인지 기능이 악화되지 않고 그 수준을 유 지하였다.

(2) 경도인지장애

경도인지장애 노인을 대상으로 한 Barnes 등(2009) 의 연구에서 기억력과 전반적 인지 기능에서 유의한 향 상을 보였으며, 3개월 후 추적평가에서도 기억력 수준을 유지하였다. 실행 기능은 유의한 수준이 아니지만 약간 의 향상을 보였고 3개월 후에도 유지되었다. Barban 등 (2016)의 연구에서는 경도인지장애 환자의 주의집중력 및 실행 기능이 유의하게 향상되었고 기억력은 약간의 향상(p=0.07)을 보였다. Herrera, Chambon, Michel, Paban과 Alescio (2012)의 연구에서는 중재 후 전산화 인지 훈련을 적용한 실험군이 일반적 인지 과제를 실시한 대조군보다 일화적 회상(recall)과 재인(recognition)의 향상으로 기억력에 유의한 효과가 있었으며 6개월 뒤에 도 지속되었다. Finn과 McDonald (2011)의 연구에서 는 주의집중력에서만 유의한 향상을 보였고, 기억력과 실행 기능에는 효과가 없었지만, 전산화 인지 훈련 항목 의 수행도 점수가 증가하였다.

(3) 정상 노인

정상 노인을 대상으로 한 Chambon, Herrera, Romaiguere, Paban와 Alescio-Lautier (2014) 연구에서는 중재를 적용하지 않은 대조군보다 전산화 인지 훈련군에서 기억 력과 처리속도가 유의하게 향상되었으며 6개월 후에는 의미 정보에 대한 기억력만 유지되었다. Barban 등 (2015)은 정상 노인이 전산화 인지 훈련 후 기억력과 실 행 기능에서 유의한 향상을 보였으며 3개월 이후에도 유 지됨을 확인하였다. Millan-Calenti 등(2015)의 연구 에서는 전산화 인지 훈련을 한 그룹에서 전반적 인지 기 능이 대조군보다 유의하게 향상하였지만 교육수준을 보 정한 뒤에는 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다.

(4) 뇌졸중

뇌졸중을 대상으로 한 Cho, Kim과 Kwon (2012)의 연구에서는 기본적인 재활 치료를 제공한 그룹보다 전산 화 인지 훈련을 받은 실험군에서 전반적 인지 기능이 유 의하게 향상되었다. 특히 노인용 인지검사(Cognition Scale for Older Adults; CSOA) 세부항목 중 실행 기능 (또는 관리 기능)에서 유의한 향상을 보였다.

Ⅳ. 고 찰

본 연구에서는 2006년부터 2016년까지 발표된 8편 의 무작위 임상실험설계 연구 논문을 분석하였다. 노인 의 인지기능을 향상시키기 위해 적용한 전산화 인지 훈 련 중재를 실시한 총 8편의 연구에 대해 방법론의 질적 평가, 연구 참여자의 유형, 종속변수를 분석하고, 국내 임 상 현장에서 전산화 인지 프로그램을 사용하는 작업치료 사들에게 기초 자료를 제공하고자 하였다. 방법론의 질 적 평가인 PEDro 척도로 살펴본 결과, 최고 점수 8점에 서 최저 점수 6점으로 모두 ‘좋음’범주에 속하여 전반적 으로 질적 수준이 높음을 알 수 있었다.

범세계적인 고령화 현상에 따라 노인성 질환에 대한 관심이 증가하는 추세이다. 노인성 질환인 치매 중 대표 적 유형인 알츠하이머병은 퇴행성 질환이기 때문에 발병 전에 예방하는 것에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있다(Bahar- Fuchs, Clare, & Woods, 2013; Lampit, Hallock, & Valenzuela, 2014). 게다가 경도인지손상은 생리학적 노화와 알츠하이머병 사이의 과도기로 50.0% 이상을 차 지하기 때문에 인지 기능 퇴행의 예방에 중요한 시기이 다(Gainotti et al., 2014).

생리학적 노화에 따라 중앙측두부(medial temporal region)를 잇는 전두나선시스템(frontostriatal system) 이 변화하여 노인의 기억력과 실행 기능에 영향을 미친다 (Salthouse, 2009). 기억력과 주의집중력은 기능적 회 로를 공유하여 긴밀한 상호작용을 하기 때문에 기억력이 손상된 경도인지손상 환자에게서는 주의집중력 손상이 동반된다(Sturm, Willmes, Orgass, & Hartje, 1997). 주의집중력은 작업기억(working memory)이라는 인지 의 처리과정에 필수 하위 요소로 포함된다고 보고 있기 때문에 주의집중력 향상이 인지 훈련의 기본적인 목표로 활용되고 있다(Miyake & Shah, 1999). 연구결과에서 도 기억력, 주의집중력, 실행 기능 등의 영역들이 주된 치료 목표로 사용되고 있음을 확인하였다.

Cho, Kim과 Kwon (2012)의 연구에서 정상 노인의 정상 표준치에 비해 확연하게 저하되는 뇌졸중 환자의 인지영역은 실행 기능이었고, 중재 후에 실행 기능의 유 의한 향상을 보고하였다. 이는 전산화 인지 훈련이 뇌졸 중 환자에게 중간정도의 효과가 있으며 통계적으로 유의 하다고 보고한 Cha와 Kim (2012)의 선행연구와 비슷 한 양상을 보였다.

알츠하이머병과 경도인지손상에 있어서 Orrell, Spector, Thorgrimsen과 Woods (2005)는 단기치료 보다는 장기치료가 중요함을 강조하였는데, 본 연구 결 과를 통해 노인의 인지적 퇴행을 예방하기 위한 중재법 으로는 전산화 인지 훈련이 효과적임을 알 수 있다. Requena, Maestu, Campo, Fernandez와 Ortiz (2006) 는 전산화 인지 훈련 중재가 치료를 받는 첫 해 동안에는 향상을 보였지만 둘째 해부터는 점진적으로 퇴화했다고 보고하였다. Gaitan 등(2013)의 연구에서 참여자들은 실험 전 치료 기간이 평균 20.56달의 치료를 받은 후였 기 때문에 천장 효과가 있었던 것으로 해석된다. 이를 보 아 알츠하이머병과 경도인지손상 환자는 1년 내의 기간 중에서도 조기에 치료가 개입되어야 하고, 장기치료로 이어지는 것이 중요함을 알 수 있다.

경도인지장애 노인의 주의집중력을 종속변수로 측정 한 3편의 연구에서 중재 후 주의집중력의 향상을 확인하 였다. 경도인지장애 대상 연구 5편은 모두 기억력을 종속 변수로 측정하였는데, 그 중 4편의 연구에서 기억력에 긍 정적 효과를 보였으며 2편에서 이것이 유지됨을 확인하 였다. Finn과 McDonald (2011)은 전산화 훈련 항목의 수행도 점수와 신경심리학적 검사 결과 간의 상관성을 분석한 결과 작업기억, 실행 기능, 학습에서 유의한 상관 관계를 나타냈다. 이는 전산화 인지 훈련으로 인한 향상 은 학습 용량(learning capacity)의 향상으로 이어져 인 지 재활적 접근이 일반화의 가능성이 있음을 제시한다. 또한 작업기억과 처리 속도(processing speed)에 문제 가 있을 경우 부호화(encoding)와 인출(retrieval)에 영 향을 미치게 되어 학습과 회상(recall) 기능이 손상된다 (Salthouse, 2009). 이에 Finn과 McDonald (2011)은 과제의 복잡성과 인지처리과정을 고려하여 중재 과정을 두 단계로 나누어서 먼저 주의집중, 처리속도, 작업기억 등의 과제에 집중하여 활성화된 이후에 기억력 과제를 하는 것이 치료 효과를 강화시킨다고 보고하였다.

정상 노인을 대상으로 한 논문들에서는 공통적으로 중 재 후 기억력이 향상되었고, 3편 중 2편의 논문에서는 3~6개월 후에도 유지되었다. Chambon, Herrera, Romaiguere, Paban와 Alescio-Lautier (2014)은 대 상자가 6개월 뒤에는 기억력 중에서도 공간에 대한 정보 가 퇴행하고 의미(semantic) 정보에 대한 기억만 지속 됨을 보고하였는데, 이를 통해 공간적 정보가 의미 정보 보다 노화로 인한 인지적 변화에 더 민감한 것을 알 수 있었다. Millan-Calenti 등(2015)의 연구에서는 정상 노인의 전반적 인지 기능이 향상됨을 확인하였지만 교육 수준을 보정한 뒤에는 유의하지 않았다. 높은 교육 수준 은 신경학적 노화로부터 신경보호작용울 하는 것으로 잘 알려져 있다(Stern, 2002). 하지만 다른 관점으로 Wilson 등(2007)의 역학조사에서는 교육수준이나 낮은 인지기능보다 최근 인지적 여가 활동의 빈도수가 알츠하 이머병 발생위험성과 더 밀접하다고 보고하였다. 정상 노인의 경우 치료나 인지 훈련을 자발적으로 받기에는 어려움이 있으므로 여가 활동을 통한 인지적·신체적 자 극과 활발한 사회적 활동을 하는 것이 건강한 노화를 위 한 좋은 방법일 수 있다(Karp et al., 2006; La Rue, 2010). 컴퓨터 개발과 인터넷 사용은 새로운 기술로 발 생한 사회적 소통의 장이 되어왔고, 이를 전산화 인지 훈 련과 병행하여 잘 활용한다면 사회적으로 단절된 노인에 게도 인지 기능 관리와 사회적 통합을 동시에 제공할 수 있을 것이다(Karavidas, Lim, & Katsikas, 2005).

전산화 인지 훈련은 임상적으로 병원에서는 작업치료 사와 함께 집중적인 치료가 가능하고, 지역사회에서도 경로당, 요양원, 복지관 등의 시설 뿐 아니라 가정에서도 적용이 가능하기 때문에 노인의 인지 기능을 향상 및 유 지하기에 효과적이다. 아직까지 전산화 인지 훈련 프로 그램의 적절한 활용 방법이 나오지 않았기 때문에 노인 의 활동 경로나 주거 환경에 따른 적용 방법을 구체화해 야 한다. 하지만 본 연구에서도 증명하듯이 노인의 인지 기능 향상 및 유지에 도움을 줄 수 있다는 것은 많은 선행 연구로 증명되어 왔다. 앞으로는 전산화 인지 훈련을 장 기적으로 적용하였을 때 노인의 다양한 요인에 미치는 효과를 살펴보는 종단연구가 진행되어야 한다. 더 나아 가서 수단적 일상생활활동 등에 일반화의 가능성을 확인 한 것처럼 앞으로는 전산화 인지 훈련이 일상생활활동의 기능적 수준, 웰빙, 삶의 질 등의 비인지 영역으로도 일반 화되는지에 대한 연구를 진행할 필요가 있다.

Ⅴ. 결 론

본 연구는 전산화 인지 훈련이 노인의 인지 기능에 어 떤 영향을 미치며, 이와 관련된 경향을 알아보기 위하여 최근 10년간 발행된 8편의 무작위 임상실험 설계 연구를 중심으로 체계적 고찰을 실시하였다. 방법론 질적 수준 은 모두 높은 수준이었고, 연구 참여자로는 경도인지손 상과 정상노인이 많았으며, 종속변수로는 기억력이 가장 많았다. 전산화 인지 훈련은 알츠하이머병 노인에게는 인지적 퇴행의 예방에 효과가 있고, 경도인지장애, 정상 노인, 뇌졸중 환자에게는 주의집중력과 기억력에서 향상 및 유지를 확인할 수 있었다. 따라서 노인성 질환에 노출 될 위험이 있는 노인은 조기에 인지 훈련에 개입되어야 하고 장기치료로 이어질 수 있어야 한다. 현재까지는 단 기치료의 효과 연구에 집중되어 있지만 추후에는 노인의 인지 기능을 향상 및 유지시키기 위한 장기적인 중재 연 구가 필요할 것이다. 본 연구는 종합적인 고찰을 통해 작 업치료 임상 현장에서 노인 인지치료의 기초자료로 활용 될 수 있을 것으로 기대한다.

Table 4

Summary of Computer-Assisted Cognitive Therapy for Cognition in Review Studies

| No. | Author (yr) | PEDro score | Participants | Intervention | Intervention intensity | Dependent variables | Measurement | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | |||||||

| 1 | Barban et al. (2016) | 7 | Mild AD (n=42)/ aged 65+ | Mild AD (n=39)/ aged 65+ | Arm-A: processbased cognitive training (pb-CT) + RT and then underwent a 3months period of rest | Arm-B: 3months period of rest and then process-base d cognitive training (pb-CT) + reminiscence therapy(RT) |

|

|||

| MCI (n=46)/ aged 65+ | MCI (n=60)/ aged 65+ | |||||||||

| Health elderly (n=61)/ aged 65+ | Health elderly (n=53)/ aged 65+ | SOCIABLE | SOCIABLE | |||||||

| 2 | Barnes et al. (2009) | 8 | MCI (n=22)/ aged 50+ | MCI (n=25)/ aged 50+ | Computer-base d cognitive training program (processing speed and accuracy) developed by Posit Science Corporation | Computer-bas ed activities (ex. Listening to audio books, reading online newspapers, computer game) | ||||

| 3 | Chambon, Herrera, Romaiguer e, Paban, & Alescio-L autier (2014) | 7 | Healthy older adults (n=15) | Leisure/ control group: healthy older adults (n=15) | Computerbased memory-attenti on training which programed in Java |

Leisure group: paper-and-Pe ncil game training Control group: none |

|

|||

Table 5

Summary of Computer-Assisted Cognitive Therapy for Cognition in Review Studies

| No. | Author (yr) | PEDro score | Participants | Intervention | Intervention intensity | Dependent variables | Measurement | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | |||||||

| 4 | Cho, Kim, & Kwon (2012) | 6 | Stroke (n=20)/ aged 55~79 | Stroke (n=20)/ aged 55~79 | Computerized cognitive rehabilitation program; RehaCom | Basic rehabilitation treatment | ||||

| 5 | Finn, & McDonald (2011) | 6 | Older persons with MCI (n=8)/ aged 60+ | Older persons with MCI (n=8)/ aged 60+ | Computerized cognitive training supplied by Lumosity Inc | No treatment (waitlist group) | ||||

| 6 | Gait n et al. (2013) | 8 | MCI & AD (n=23)/ aged 57~85 | MCI & AD (n=16)/ aged 57~85 |

CBCT & TCT FESKITS Estimulacin Cognitiva’ Version 2.5 (Fundaci Privada Espai Salut, 2009) |

TCT |

|

|||

| 7 | Herrera, Chambon, Michel, Paban, & Alescio-L autier (2012) | 6 | Amnestic MCI (n=11)/ aged 56~90 | Amnestic MCI (n=11)/ aged 56~90 | Computer-based memory-attenti on training which programed in Java | Cognitive activities | ||||

| 8 | Millan- Calenti et al. (2015) | 8 | Healthy older adults (n=80)/ aged 65+ | Healthy older adults (n=62)/ aged 65+ | Computerized cognitive training application Telecognitio | None |

|

|||

[i] AD: Alzheimer’s Disease, AFI: Attention Function Index, A-MCI: Amnestic Mild Congnitive Impairment, BIQ: Basic IQ, BNT: Boston Naming Test, CANTAB test: Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery, CBCT: Computer-Based Cognitive Training, COWAT: Controlled Oral–Word Association Test, CSOA: Cognition Scale for Older Adults, CTT-A: Color Trails Test part A, EIQ: Executive IQ, FIQ: Full-scale IQ, GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale, IADL: Instrument Activity of Daily Living, IGT: Iowa Gambling Task, LFI: Language Function Index, LLART: Letter-Location Association Recall Test, MCI: Mild Congnitive Impairment, MFEM: Memory Failures in Everyday Memory, MFI: Memory Function Index, MFQ: Memory Functioning Questionnaire, PPTT: Pyramids and Palm Trees Test, RAVLT: Auditory Verbal Learning Test, RBANS: Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Cognitive status, RL/RI-16: Sixteen-Item Free Reminding Test, ROCF: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, RSE: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, RT: Reminiscence Therapy, SD: Standard Deviation, STAI-S: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory State, TCT: Traditional Cognitive Training, TMT: Trail Making Test, VFI: Visuospatial Function Index, WAIS III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III, WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, WM: Working Memory, WMI: Working Memory Index, WMS III: Wechsler Memory Scale III