Ⅰ. Introduction

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), in 2016 an estimated 429,000 children were diagnosed with cancer from birth to 19 years of age and survived. However, mortality rates for this pediatric oncology population have decreased by nearly 50 percent within the same time span (NCI, 2016). Based on this knowledge, the number of child and adolescent cancer survivors is projected to grow, with child cancer evolving from being a fatal diagnosis to a chronic condition (Robinson & Hudson, 2013). Individuals diagnosed with cancer and those receiving oncological treatment may have a host of impairments resulting in loss of ability to perform daily occupations. These daily occupations include but are not limited to selfcare, leisure, social and school activities (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2011). Pediatric oncology patients can also present with psychosocial complications as well-being becomes increasingly relevant given the pervasive long-term effects of cancer (Hicks, & Lavender, 2001; Nayak et al., 2017). Psychosocial complications such as decreased mood and elevated stress levels can adversely impact their QoL (Mody, Prensner, Everett, Parsons, & Chinnaiyan, 2017; NCI, 2016).

The purpose of occupational therapy for these individuals is to help patients engage in life as independently and safely as possible with the primary goal of improving their QoL through improvements in function (Liddle & McKenna, 2000; Longpre & Newman, 2011). The purpose aligns with the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which defined QoL as one of the three most important psychosocial outcomes for these patients (1996). According to the AOTA (2019), Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) can be a meaningful way to connect with individuals, encourage participation, and improve QoL.

Scientific evidence indicates that AAI can further improve occupational therapy sessions in a variety of ways. For example, Majić, Gutzmann, Heinz, Lang and Rapp (2013) found in a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) that utilization of AAI resulted in diminished symptoms of agitation, aggression and depression among nursing home residents with dementia. Occupational therapy improves the QoL of patients by promoting independent engagement in meaningful occupations , while AAI improves the QoL of patients by implementing animal interaction as an alternative therapeutic modality (AOTA, 2014; Nimer & Lundahl, 2007; Pergolotti, Williams, Campbell, Munoz, & Muss, 2016).

Currently, no systematic reviews have examined AAI with the potential use for occupational therapy practice that specifically target this population. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the psychosocial benefits of AAI interventions with pediatric oncology patients and its efficacy for enhancing overall QoL. Studies included in this systematic review included AAI, Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) and Animal-Assisted Activities (AAA).

Ⅱ. Methods

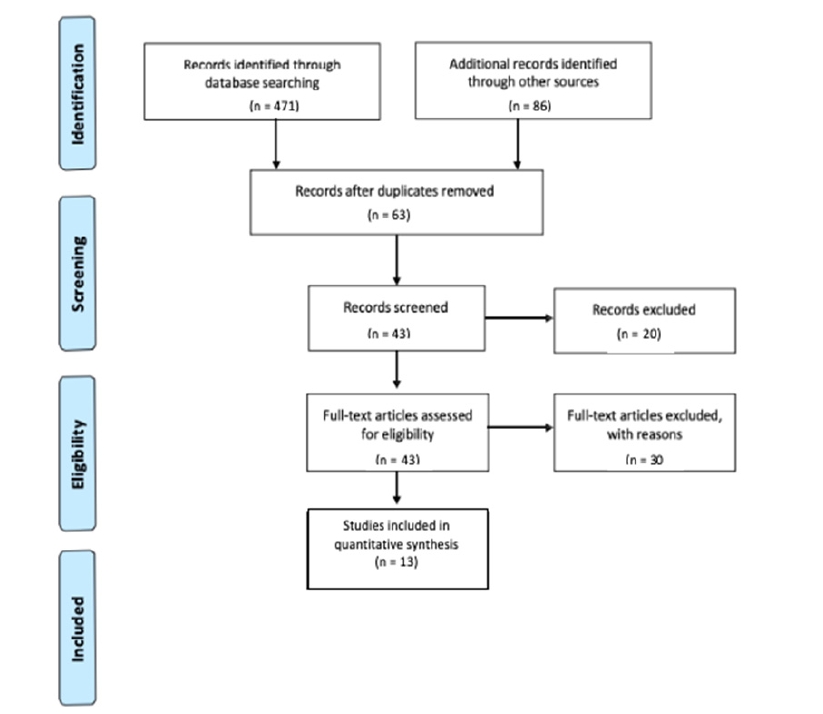

This systematic review was conducted between January-August 2019, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines as specified by the AOTA (2017). The diversity of intervention targets and outcome measures were too varied to complete a meta-analysis (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). The list of search terms for the review was developed using medical subject headings found on PubMed, in addition to subject terms from CINAHL. Table 1 lists the search terms used. Article citations and abstracts were reviewed from PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT), Journal of Oncology, SCOPUS, and OTSeeker. Additional sources were reviewed from evidence-based medicine reviews including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register. Abstracts from other focused questions and those found by hand searching journals were included in the reference list (refer to Figure 1).

Table 1

Search Terms

Titles and abstracts were initially reviewed by individuals from the research group (AS, KV, PR, KP, and AN) to select articles for further evaluation. The screening process was repeated to review the full text of potential articles. Literature reviews and other studies with insufficient or limited scope of information were excluded. After screening and discussion, 13 final articles were selected for this review, with evidence ranging from Level I to Level IV as described by Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes and Richardson (1996).

Inclusion criteria for studies were: (1) participants were pediatric patients undergoing oncological treatment, (2) included quantitative psychosocial outcomes, (3) examined AAI interventions that used dogs within the respective studies, (4) interventions were completed in the hospital or clinical setting, (5) purpose of AAI was to improve psychosocial outcomes, and (6) must be published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals. Original inclusion criteria required that studies were published within the last ten years, but due to the lack of research available, inclusion criteria were expanded to include articles published within the last 20 years. Studies were excluded if (1) all participants were over the age of 19 years, (2) not on a pediatric hospital unit, or were conducted in settings where pediatric oncology patients would not be located; (3) were from non-peer-reviewed research literature, dissertations, theses, presentations, and conference proceedings; or (4) explicitly stated exclusion of pediatric oncology patients.

Ⅲ. Results

Thirteen peer-reviewed studies published between 2002 and 2019, were examined to evaluate the association of AAI on psychosocial outcomes. Thirteen AAI studies were divided into four psychosocial domains of QoL: pain (Barker, Knisely, Schubert, Green, & Ameringer, 2015; Braun, Stangler, Narveson, & Pettingell, 2009; Chubak et al., 2017; Silva & Osório, 2018; (Sobo, Eng, & Kassity-Krich, 2006), mood (Branson, Boss, Padhye, Trotscher, & Ward, 2017; Kaminski, Pellino, & Wish, 2002; Silva & Osório, 2018; Osório & Silva, 2017), stress (McCullough et al., 2018; Silva & Osório, 2018; Sobo et al., 2006), and anxiety (Barker et al., 2015; Branson et al., 2017; Chubak et al., 2017; Hinic, Kowalski, Holtzman, & Mubus, 2019; McCullough et al., 2018; Osório & Silva, 2017; Tsai, Friedman, & Thomas, 2015). Additionally, parents’ and caregivers’ perceptions of the patients’ QoL were included (Caprilli & Messeri, 2006; Kaminski et al., 2002; Moody, King, & O’Rourke, 2002). The articles consisted of randomized control trials, descriptive studies, case reports, and pilot studies. Refer to Table 2. for an overview of the included studies.

Table 2

Evidence Table

To quantitatively assess the effectiveness of AAI on the specified domains of QoL, various ageppropriate outcome measures were used. Four articles used the State Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC), three used the Wong-Baker FACES, two used the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL), two used the Child Stress Symptoms Inventory, two used the Quality of Life (QoL) Evaluation Scale, two used the Adapted Brunel Mood Scale, one used the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), one used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS-C), one used the Reynolds Child Depression Scale, one used the Animal Assisted Treatment (AAT) Assessment Questionnaire, one used the Child Depression Inventory (CDI), one used the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM), one used the Distress Thermometer, one used the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), one used the Patient Related Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), and one used the Brisbane AAT Acceptability Test (BAATA). Last, two studies stated the use of a general questionnaire for the collection of background demographic information. Given that several of the studies evaluated more than one domain of QoL, more than one outcome measure was used within some of the respective studies.

1. Pain

Pain was defined as unpleasant physical sensations (Lumley et al., 2011). Four of the five studies found statistically significant decreases in pain following animal-assisted intervention (Braun et al., 2009; Chubak et al., 2017; Silva & Osório, 2018; Sobo et al., 2006). Braun et al. (2009) found that participants in the treatment group experienced statistically significant reductions in pain levels compared to the control group (p = 0.006), following one 15-20-minute AAI session. Silva and Osório (2018), found that patients who participated in three 30-minute sessions of animal-assisted therapy had significantly reduced pain (p = 0.046). Chubak et al. (2017), found a statistically significant decrease in pain levels following one 20-minute AAI session (p = 0.02). Sobo et al. (2006) found a statistically significant reduction in perceived pain reported by participants following intervention (p = 0.001). One of the five studies did not find significant changes in pain. Barker et al. (2015) randomly assigned 40 pediatric patients to an animal-assisted intervention compared to an active control group and found decreases in pain with the AAI group, however, results were not significant (p = 0.92).

2. Mood

Mood was defined as an emotional state inclusive of depressive symptoms (Flett, Blankstein, & Obertynski, 1996). Two out of four studies found statistically significant associations with AAI and mood improvements (Osório & Silva, 2017; Silva & Osório, 2018). And one study found results approaching significance (Kaminski et al., 2002). In a two-group, non-randomized study, Kaminski et al. (2002) compared AAI and child-life activities. Children in the AAI group showed results approaching significance in more instances of positive affect and touching than the comparison group that demonstrated more instances of neutral affect (p = 0.05). Osório and Silva (2017) examined depressive symptoms in 10 children undergoing oncological treatment who received weekly AAI open group sessions; statistically significant reduction in depression indicators were found following AAI. Silva and Osório (2018) found that levels of irritation and depressive symptoms were significantly improved (p = 0.041).One study found increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect following AAI; however, the differences were not statistically significant when compared to the control group (p = 0.91); (Branson et al., 2017).

3. Stress

Stress was defined as the state of emotional tension (Rotenberg & Boucsein, 1993). Three studies evaluated the implications of animalassisted intervention as a stress-reducing intervention for pediatric oncology patients and all three found statistically significant results (McCullough et al., 2018; Silva & Osório, 2018; Sobo et al., 2006). McCullough et al. (2018) conducted a multi-site randomized control trial and found significant improvements in stress reduction, (p=0.008), in the AAI group compared to the control. Silva and Osório (2018) found statistically significant improvements in stress (p = 0.005) following three open group AAI sessions. Sobo et al. (2006) sampled 25 pediatric oncology patients and found decreases in emotional pain scores before and after AAI were statistically significant (p = 0.001).

4. Anxiety

Anxiety was defined as recurring thoughts of worry over an extended period of time (Matthews, 1990). One of seven studies which investigated the association of AAI and anxiety levels found significant results (Chubak et al., 2017). Four of the seven studies found that AAI did lead to decreased anxiety scores when solely comparing pre- and post-intervention values for the AAI groups; however, the results were not significantly different compared to the control groups (Branson et al., 2017; Hinic et al., 2019; McCullough et al., 2018; Osório & Silva, 2017). Chubak et al. (2017) found a statistically significant decrease in worry was found following the animal-assisted intervention (p <0.01). Barker et al. (2015) did not find significant changes in anxiety ratings between the AAI and control groups (p = 0.67). Branson et al. (2017) did not find statistically significant differences between the groups, however, increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect were larger in the AAI group (p = 0.31). Hinic et al. (2019) found statistically significant within group decreases in pre- and post-scores for state anxiety for both the intervention and control groups; however, the difference in decreased anxiety levels between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.537). McCullough et al. (2018) did not find statistically significant differences (p = 0.559) between the intervention and control groups over time on any outcome measures. Tsai et al. (2010) found that anxiety level reductions were not statistically significant (p = 0.67) when compared to the control group.

5. Parents’ and Caregivers’ Perspectives of Quality Life on Pediatric Oncology Patients

Parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives of QoL were dependent upon whether they believed the AAI improved QoL of the pediatric patient. Three of three studies found that parents’ and caregivers’ perceptions of AAI improved patient’s QoL (Caprilli & Messeri, 2006; Kaminski et al., 2002). Kaminski et al. (2002), measured caregiver ratings on patient’s QoL, in addition to the child’s selfperceived mood reports before and after intervention. Per caregiver report, patients in the pet-therapy group received statistically significantly higher ratings in happiness compared to the control group after treatment (p<0.05). Caprilli and Messeri (2006) found that of the 46 parents who had completed the questionnaire, 100% of the parents reported that the interaction between their children and the animals was favorable, and 94% believed that the program could benefit their child. One study found that caregivers did not perceive significant improvements in QoL for the patients. Moody et al. (2002) disbursed 244 questionnaires and collected 195 responses, 12-weeks after introduction of the pet-therapy program. Statistical significance was not stated for the caregivers’ perceptions of the patients’ QoL; however, scores for the BAATA Test were recorded as modal score ‘1’ indicating ‘strong agreement’ for the program’s effectiveness in relaxing and distracting the children.

1) Risk of Bias

Adhering to Higgins, Altman and Sterne (2011) use of methods design, all 13 studies included in this systematic review were evaluated for selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting biases risks (refer to Table 3.). The studies evaluated posed risk in multiple categories based on the design of the studies. It was difficult to blind the participants to their placement in a group because the intervention required a live animal to be present, making it easily known into which group they would be placed. Random selection of participants was also made difficult because of the medical contraindications and risks posed on the children by presenting a live animal. Multiple considerations were considered, including whether patients were immunosuppressed. The AOTA (2017) guidelines served as a model for thorough evaluation and assessment of each article’s study design and their potential risks for bias (refer to Table 2).

Table 3

Risk of Bias Table

Ⅳ. Discussion

Based on the findings in this review, it can be concluded that AAI may be useful for the reduction of negative symptoms associated with undergoing oncological treatment for pediatric patients. Each psychosocial outcome (i.e. perception of pain, stress, anxiety, mood, and parent and caregiver’s perceptions of QoL) and the intervention protocols (refer to Table 2 for brief intervention descriptions) should be evaluated to determine whether it would be appropriate for a specific setting and the individual patient. Potential factors, i.e. infection control policies, handler experience, and hand hygiene, should be considered due to the medical complexity and immunocompromised status associated with the oncology population (Khan & Farrag, 2000).

Strengths of this study lie in the use of an occupational therapy lens for critical evaluation and use of quantitative data to evaluate psychosocial outcomes. An additional strength is the added perspective of including data from parent and caregiver input. Caregivers witness changes in mood and affect that immediate post-intervention measurements may not detect. Occupational therapy is grounded in treating the whole person , thus this study provides further insight on how occupational therapists can maximize holistic practice and intervene beyond isolated components of physical dysfunction (AOTA, 2014).

Limitations were found upon completion of this review. The use of the terms AAA and AAT were not clearly defined by each study and appeared to have been used interchangeably within several of the studies. Therefore, it was not reasonable to compare outcomes from these types of AAI in this review. The differentiation of identified AAA versus AAT interventions, however, did not impact the number of significant findings for the domains of QoL. Seven of the studies (Barker et al., 2015; Chubak et al., 2017; Moody et al., 2002; Osório & Silva, 2017; Silva & Osório, 2018; Sobo et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2010) included in this review involved small sample sizes of no more than 50 participants, and only three (Barker et al., 2015; Branson et al., 2017; McCullough et al., 2018) of the 13 studies were randomized. Additionally, the studies by Barker et al. (2015) and Branson et al. (2017) did not provide a power analysis to determine sample sizes, which may have affected the significance of results. Nearly half of the studies evaluated in this review did not utilize a control group for comparison of outcomes. Finally, the length of the studies varied from two 6-minute sessions to 20-minute sessions per week for four months, which may have affected the association of AAI on the respective domains of QoL.

Findings from this review suggest that more studies are needed to examine the long-term effects of AAI on the pediatric oncology patients. Additionally, more studies that incorporate animals into rehabilitation are necessary to evaluate its association to motivation. Further studies on AAI have the potential to improve outcomes of occupational therapy by increasing participation and goal attainment (AOTA, 2019). Occupational therapy practitioners can consider the use of AAI during occupational therapy treatment sessions to serve as a distraction and short-term coping strategy for children undergoing oncological treatment. Additionally, AAI can enhance social interaction between the patient and therapist. By completing an occupational profile and understanding the patient’s interests, AAI can serve as a patient motivator and reward throughout therapy sessions (Vroman & Collins, 2015).

The findings of this review have the following implications for occupational therapy practice and research:

• AAI is a meaningful way of connecting with pediatric oncology patients during occupational therapy sessions; thus, incorporating AAI can further the patient-therapist relationship and client-centered practice.

• Occupational therapists could incorporate AAI to potentially increase functional participation in therapy sessions.

• Occupational therapists may utilize AAI as a preparatory activity or in conjunction with therapeutic intervention for occupational therapy sessions.

• Further occupational therapy intervention and AAI-centered studies must be conducted to evaluate their effectiveness to improve QoL for pediatric populations, within the hospital, community, and home settings.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

This systematic review examined the effects of AAI on the target population of pediatric oncology patients with the intention of determining its utility in occupational therapy practice. Mixed results were found overall regarding the benefits of AAI for the identified domains of QoL (i.e. perception of pain, stress, anxiety, and mood, in addition to parents and caregivers’ perceptions of QoL). Moderate strength was found for the domains of pain, stress levels, and mood, supporting the benefits of using AAI for the pediatric patients undergoing oncological treatment. Low-level evidence was found to support the use of AAI for anxiety reduction with this population. These findings suggest that AAI may be used as a short-term coping method, since stress, mood, and pain were improved with AAI. Conversely, anxiety had a lower number of studies which found significant results, indicating that AAI may be beneficial for impacting psychosocial QoL short-term, rather than long-term. Based on these findings, occupational therapists may consider implementing AAI to manage pain symptoms, improve mood, and alleviate stress among pediatric oncology patients. Further research on AAI for pediatric oncology patients is recommended to support the efficacy of AAI in occupational therapy practice.