Ⅰ. Introduction

Recently, scholarly attempts to understand practitioners’ reality and everyday work, and resulting findings on perceived values, barriers, and obstacles in using Occupation-Based Practice (OBP), have increased. In an online survey study with 594 members of the American Society of Hand Therapists, Grice (2015) found that the primary reason for not utilizing occupation-based assessment was the time limitation, followed by unfamiliarity. Participating practitioners in Grice’s study reported that occupation-based assessment and intervention facilitated functional outcomes and a better acceptance on clients’ part as to why they were receiving given therapeutic activities, and practitioners also noted that clients were more motivated if they had a specific goal and could identify their goals through occupation-based assessments. In a Delphi study in an Asian context, Daud, Yau, and Barnett (2015) found that both client- and occupational therapistrelated factors, logistical issues, the credibility of the occupation, and contextual factors were challenges to implementing OBP in clinical practice. Participating therapists concurred that OBP is an occupational performance intervention that matches clients’ goals, is meaningful, and should be performed within the client’s context. Yet they also felt that preparatory and purposeful methods could be incorporated into OBP.

Across the geo-sociopolitical landscape, researchers in South Korea have also documented the effects of OBP and made efforts to develop competency indicators for OBP and understand practitioners’ perceptions and use of OBP. In a survey study with a convenient sample of 293 therapists, Chang (2017) found that 52% of the participants reported using OBP. Kang, Kim, and Chang (2019) also surveyed a convenient sample of therapists in a different location and found that participants of their study reported only a modest level of awareness and implementation regarding OBP. Furthermore, Yoo, Lee, Kim, and Han (2016) reported the recent trend of Korean researchers’ focus on OBP by examining the independent variables of published studies from 2011 to 2015. These concerted research efforts signify a transformational power to attune to the core of client-centered practice (Schell & Gillen, 2019). Practitioners’ concerns over-and perceived difficulties and low adoption level of-OBP, as found in studies, clearly reflect both the reality and shared identity and high integrity valuing toward OBP, calling for more educational and research efforts on resources and/or guidelines to support practitioners.

Fisher (2014) argued that using the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) can be an OBP. MOHO focuses on the whole person and the person’s adaptation as an occupational being. Therapists and clients who use the lens of MOHO see factors influencing one’s participation such as volition (i.e., motivation for occupation composed of sense of capacity and self-efficacy, values, and interests), one’s roles and daily routines while performing one’s life occupation (habituation), the performance capacity embedded in one’s body, and the environment where all the components work together and emerge as enabling skills to perform an occupation (Taylor & Kielhofner, 2017). Because MOHO permits a wide selection of assessments to be chosen to confront the complex nature of OBP, is widely used internationally, and provides a unified terminology and coherent frame in which to work, narrowing issues regarding OBP using MOHO can be useful for practitioners, researchers, and educators on many levels. A honed OBP application with anchoring theory can be used for theory refinement, the development of professional development resources, and documentation of outcomes needed for policy change. Researchers have conducted studies in the United States on the use of theory, using MOHO with systematic random samples to evaluate knowledge, attitudes, use of assessments, and the perceived benefits and challenges of using MOHO (Lee, Kielhofner, & Fisher, 2008). In addition, with a purposive sample of expert groups in the United Kingdom, Lee et al. (2013) discerned the degree to which participants adopted the model and identified the occupational needs noted by therapists based on theory. Employing these existing measures and gathering hands-on experience and perspectives of practitioners in Korea via a nationwide survey could elicit information that may be useful in taking incremental steps toward much-aspired-to OBP.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was, first, to gather empirical information about occupational needs perceived by therapists; second, to describe whether therapists are well equipped to adopt the theory; and third, to incorporate perceived strategies to apply theory-guided OBP using MOHO, with the goal of creating a more OBP-tailored practice environment. In particular, we designed the following inquiries encompassing three theme areas:

• How do practitioners perceive the necessity of occupation-focused practice? What are the occupational needs seen among clients according to the theory-driven six occupational functioning areas?

• How are practitioners ready to use MOHO-driven OBP? What educational supports have they received, how much time was spent, and how useful did they find those methods? To which knowledge resources have they been exposed? What is the perceived knowledge of MOHO assessments and adoption level of MOHO? And how much do they desire to apply MOHO-based OBP?

• What are the perceived strategies for mastering MOHO to competently apply OBP? How do they value/find the ease/usefulness of theory learning components (i.e., theory, assessment, goal setting, and therapeutic reasoning)? For whom and where do practitioners anticipate using MOHO? What kinds of resources do practitioners feel are necessary when using MOHO and identify as effective methodologies for a professional development program?

By delineating the clients’ occupational needs, supports and barriers to therapists’ implementation of OBP, and perceived strategies, we hope that the findings of this study will shed light on the rationale for, and external and internal factors affecting, the ongoing transformation of practice in the service of clients.

Ⅱ. Methods

1. Research design

We conducted this study using a survey methodology, utilizing an online survey system called Survey Monkey (https://ko.surveymonkey.c om/); the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Daegu University (IRB No. 10406 21-201707-HR-022-02).

2. Participants and procedure

Korea had approximately 13,000 licensed occupational therapists at the time of the study. A minimum sample size for a given population (i.e., 9,740 licensed members of the Korean Association of Occupational Therapists), with 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error, was about 370 (Barlett, Kotrlik, & Higgins, 2001). To maximize the representativeness of the target population and the generalizability of the study, we employed a systematic random sampling method. With the average response rate for online surveys in mind, we sent the invitation letter to 1,100 email addresses and issued a follow-up invitation two more times, as recommended by Forsyth and Kviz (2017). The invitation reached 468 practitioners during the three weeks of the study period, of whom a total of 121 responded-for a response rate of 25.9%. Of those, we analyzed only 111 eligible responses, per the inclusion criteria (i.e., practicing within 3 years of the study, retrospectively).

3. Survey instrument

We developed the survey instrument for this study as recommended in the literature (Forsyth & Kviz, 2017). First, we invited 13 therapists who attended the MOHO-related national workshop to generate content relevant to the purpose of the study and appropriate to the context of Korea. We incorporated information gathered from a pilot survey into the construction of the questionnaire, which was modified from previous MOHO use studies in the United States and United Kingdom. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for questions concerning occupational needs was .741; that for readiness was .935; and it was .970 for the perceived strategies section of the questionnaire.

4. Data Analysis

We analyzed data using the Statistical Program for the Social Sciences software program, version 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and used descriptive statistics to answer the study questions. All percentages reported are based on valid responses, and frequency data represent the actual number of people who responded to each question. We calculated a Spearman’s Rho to examine the magnitude of association among categorical variables.

Ⅲ. Findings

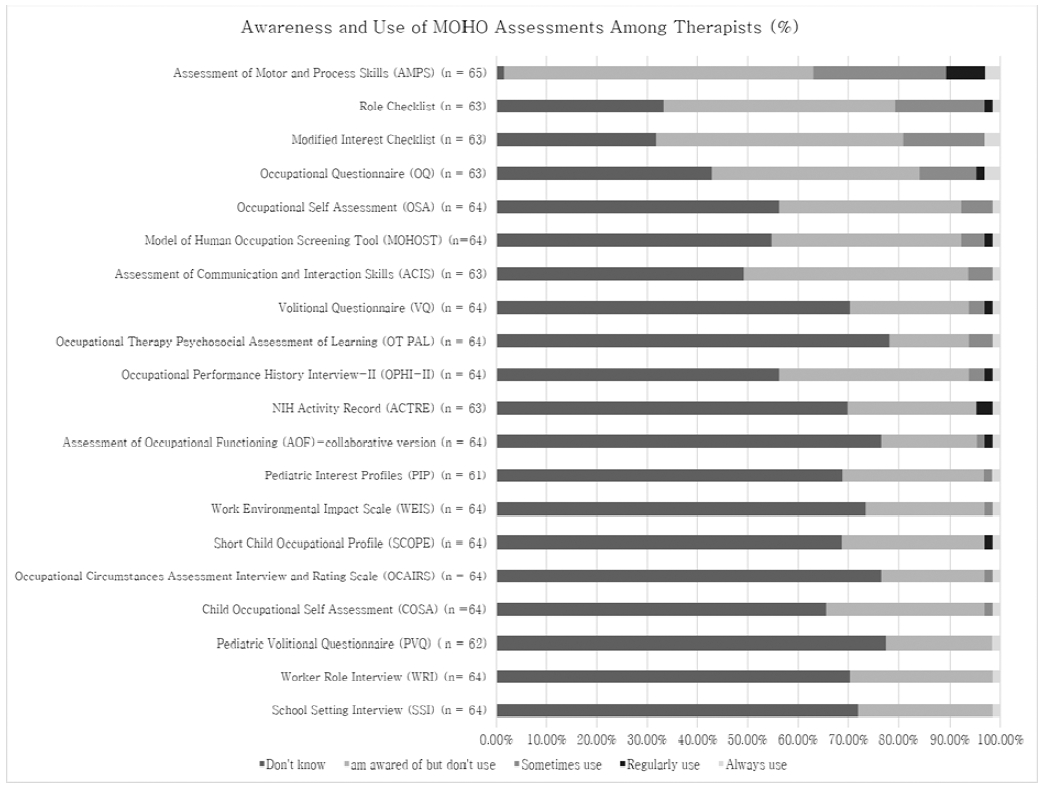

1. Characteristics of respondents

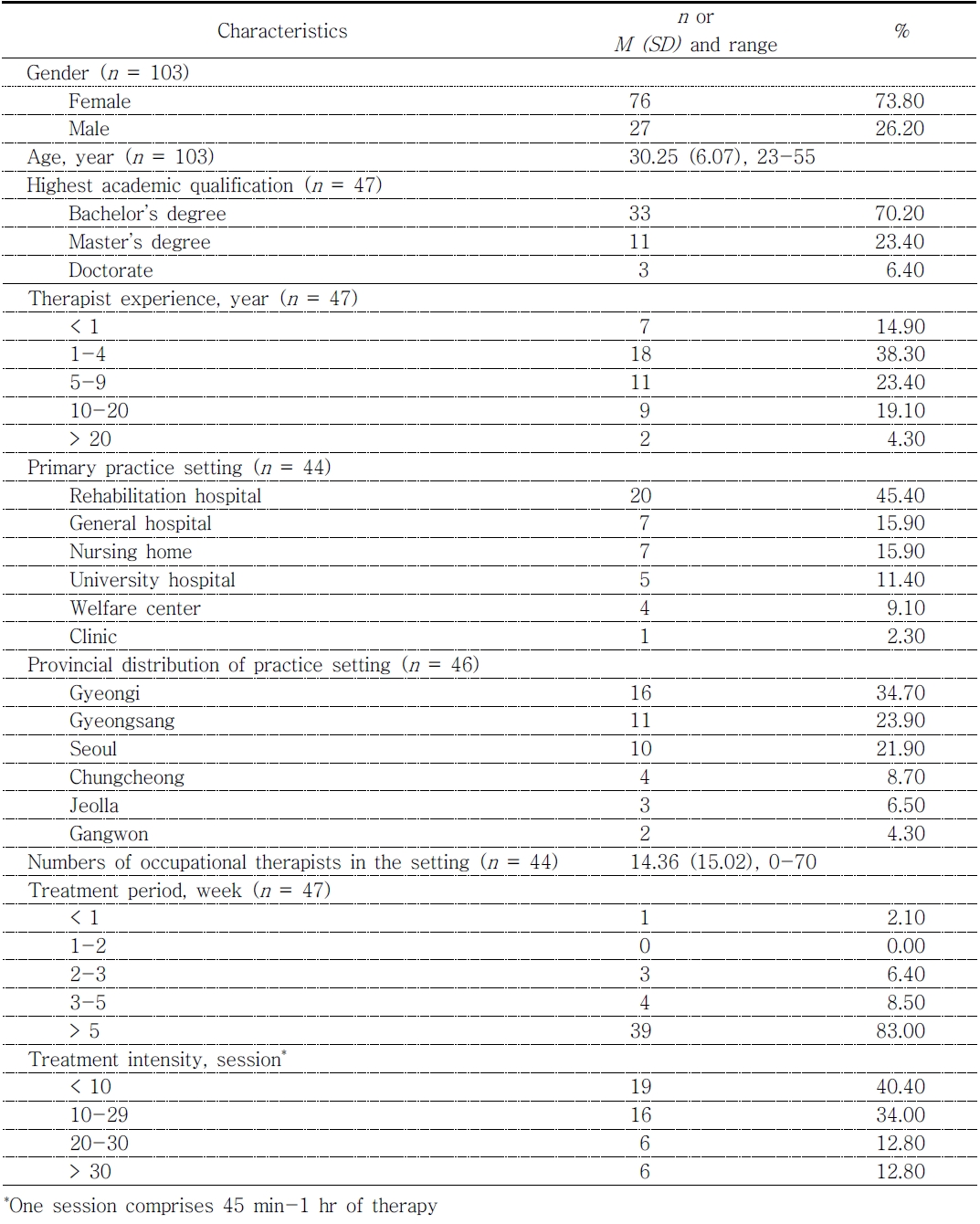

Most participants were female (73.8%). Their ages ranged from 23 to 55 (mean = 30.25, SD = 6.07). Of the respondents, 70.2% held a bachelor’s degree; the levels of professional experience varied; Gyeongi province had the highest number of practitioners (34.8%). Detailed demographic information is depicted in Table 1. Respondents were working with adults the most (48.9%) and older adults over 65 years old (25.5%), followed by children (17.0%), adolescents (4.3%), and early intervention (4.3%). The impairment/problem areas frequently or almost always seen by respondents were, in descending order, movement/mobility (82.9%), cognitive/perceptive/intellectual/learning disabilities (80.9%), sensory issues (70.2%), and emotion/behavior/mental health/substance related (42.6%).

2. Perceived needs of OBP and clients’ occupational needs reported by practitioners

When we asked participants about the degree to which they felt OBP was needed in general on a 4-point Likert scale (1: definitely not, 2: probably not, 3: probably, 4: very probably), most indicated that OBP was needed in practice very probably (54.5%) or probably (41.6%). For specific reasons (these were statements asked in a U.S. survey study), they thought MOHO was helpful for client-centered practice (“It helps me to do a client-centered practice. As a core of OT, occupation-focused practice is very important”; 98.6%), professional identity (“Focusing on occupations is meaningful as an occupational therapist, and it is a basis for OT practice”; 96.0%), and treatment process (“MOHO structures my thinking about the occupational therapy process [e.g., activity analysis, treatment, caregiver consultation, objective goal setting]”; 93.4%).

We then asked about therapists’ perceived occupational functioning of their clients linked by MOHO theory; these six areas were from the model of human occupation screening test (MOHOST; Parkinson, Forsyth, & Kielhofner, 2006; i.e., motivation for occupation, patterns of occupation, communication/ interaction skills, process skills, motor skills, and environment). The most problematic area reported was roles and routine, corresponding to “habituation,” of MOHO theory, followed by the motor skills area (see Figure 1).

3. Readiness for implementation of MOHO-based OBP

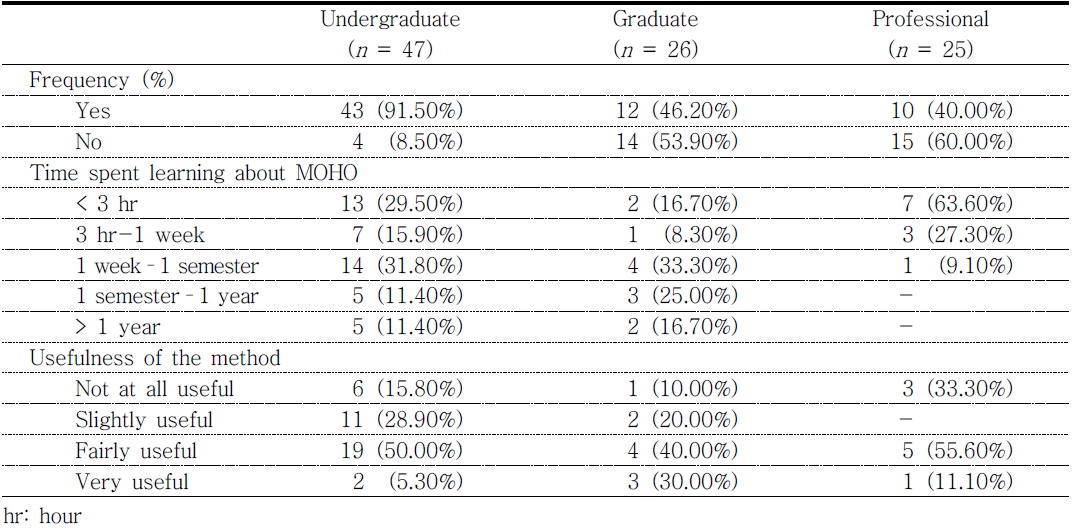

Respondents reported that they had learned the most about MOHO in their undergraduate program, but the time spent learning MOHO varied at the undergraduate level from less than 3 hr to more than 1 year (see Table 2). Therapists who had learned MOHO at the graduate level indicated a longer time spent and higher level of usefulness compared to experiences at different levels. Understandably, we found those who had learned about it at a professional level such as workshops had studied it for a much shorter period, and the usefulness was found to be the least.

Table 2

Courses, Time Spent Learning About MOHO, and Perceived Usefulness on Three Different Levels of Educational Experience

|

We also asked therapists about which MOHO resources they were exposed to among textbooks, articles, and/or case videos. The most common resource among six different versions of the MOHO textbook (i.e., MOHO 1st to 3rd edition, MOHO 4th edition, translated MOHO 4th edition, and MOHO 5th edition) was the translated version of the 4th edition, which had been read by about one fifth of respondents, whereas six therapists indicated they were acquainted with the 5th edition, which had just released at the time of the study. Among the respondents, 27 reported that they had read up to 10 MOHO-related articles, 8 indicated they had read more than 10 articles, and 10 reported they had watched MOHO-related case videos. The number of different resources ranged up to 7, with 1.4 methods used on average.

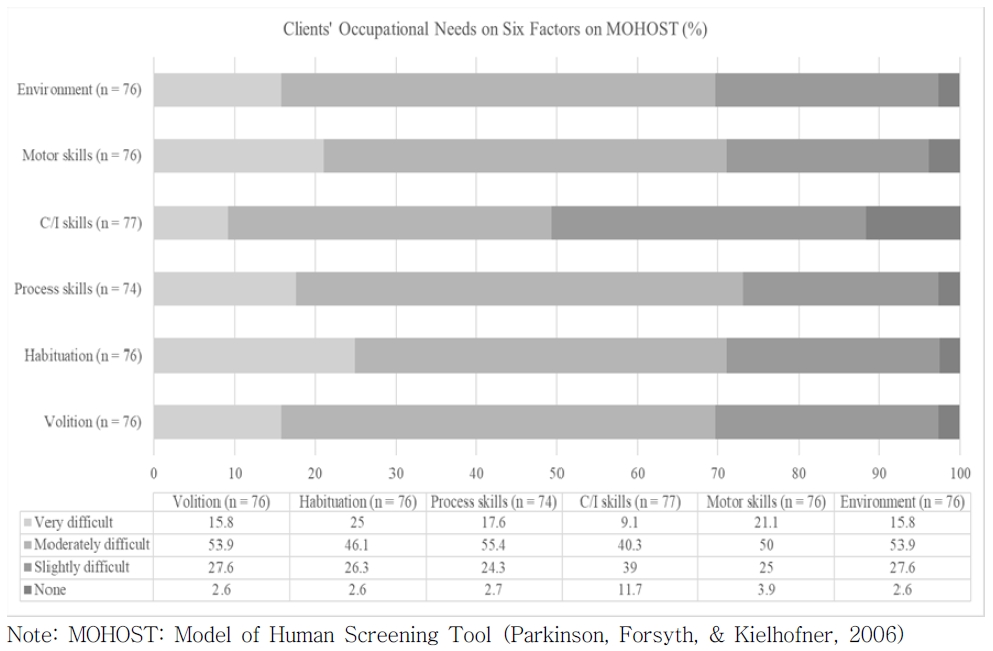

We then asked participants about the degree to which they were exposed to MOHO assessments. The respondents reported that the top five assessments they were using had assessment of motor and process skills at the top, followed by the modified interest checklist, role checklist, occupational questionnaire, and occupational self-assessment (see Figure 2).

The respondents reported their current adoption level of MOHO in their everyday practice as follows: No use yet (27, 45.8%); “Trying to reason with MOHO and learning more about it and its assessment” (22, 37.3%); “Starting to reason with MOHO and were learning to use the assessments” (8, 13.6%); or “Consistently and confidently reasoning with MOHO and helping others to learn this model” (2, 3.4%). In contrast, the extent to which therapists responded for the desire to adopt MOHO at four levels was as follows : “I’d rather not adopt” (10, 16.7%); “I’d rather adopt the MOHO” (26, 43.3%); “I want to adopt MOHO” (7, 15.3%); or “I very much want to adopt MOHO” (7, 11.7%).

4. Perceived strategies to implement MOHO-guided OBP

Next, we enquired about therapists’ perceived strategies to incorporate MOHO into practice via several questions. On average, respondents anticipated that about 7 months of studying time would be needed. When we asked therapists about with what population they anticipated applying MOHO-based OBP, they indicated the community setting (n = 34) the most, followed by schools/school-based OT (n = 29), outpatient rehab (n = 28), inpatient rehab (n = 26), home-based OT (n = 23), private practice (n = 20), and nursing hospital (n = 19) as MOHO-appropriate practice settings/populations.

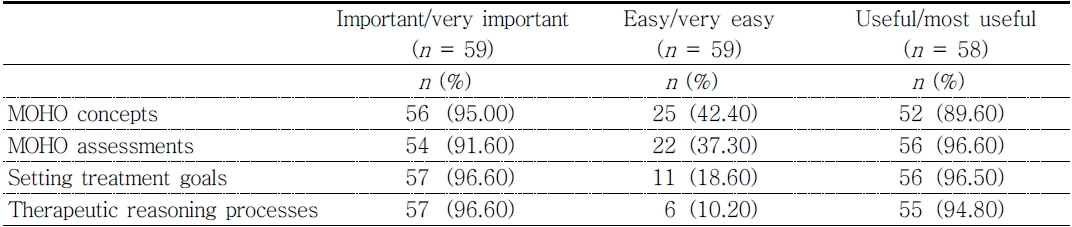

We also asked about each of the four MOHO learning components: MOHO concepts, MOHO assessments, setting treatment goals, and therapeutic reasoning processes, as drawn from the U.S. national study, in terms of how “important,” “easy,” and/or “useful” respondents found them for conducting MOHO-based OBP. The results show that overall, they valued these components and found them useful for use in practice roughly equally; however, they found setting treatment goals and therapeutic reasoning processes to be the hardest constructs and processes to adopt (see Table 3).

Table 3

Value, Ease and Usefulness of MOHO Concepts, Assessments, Goal-Setting, and Therapeutic Reasoning Process

|

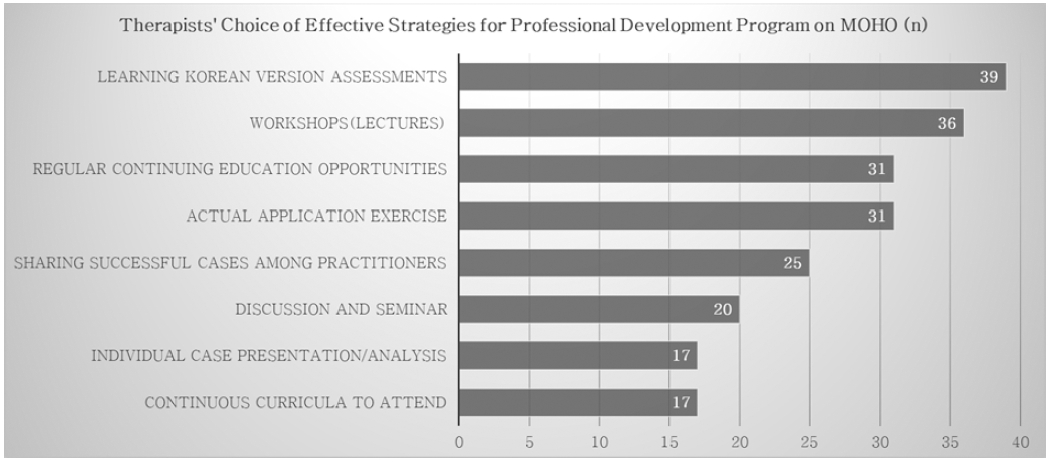

Next, we asked participants, when they were about to apply MOHO in their specific context, how much they would feel factors, which were deemed to be necessary in the pilot survey study, were needed. We ordered these factors from most needed to least needed as follows: first, therapist’s will/interest (70.2%); second, work environment/ cooperation from organization and/or case synthesis experience (fieldwork; 68.8%); third, translation of assessments (64.6%); fourth, obtainment of MOHO manual/assessment forms (58.3%); fifth, curriculum on theory learning (44.7%); sixth, advertisement (43.8%); and seventh, availability of supervision (35.4%). When we asked respondents whether a translated version of the assessment would be required for OBP, 43 (91.5%) indicated they were in favor of the translated assessments.

Moreover, the participants specifically responded to a question that asked about the methods they employed for innovative continuing education with the goal of building professional efficacy; the responses are indicated in Figure 3. They emphasized that MOHO assessments needed to be properly translated, that education support needed to be available, and that they needed to be able to regularly access those resources along with actual application experiences.

Finally, we analyzed what factors were associated with the extent of MOHO use. As a preliminary finding, we found there was an association among experiences at different education levels, time spent learning about MOHO, adoption levels, and therapists’ reported desire to use MOHO. Detailed magnitudes of the associations are depicted in Figure 4. Practitioners who indicated that they wanted to use MOHO more also reported more positively on their learning experience, regardless of demographic information, such as age, gender, experience as OT, client population, and practice setting. Perceived usefulness was also associated with the time spent learning about it. Furthermore, the association was between more use of MOHO and greater desire to use it.

Ⅳ. Discussion

In this study, we described therapists’ perception of the rationale for, supports for therapists’ readiness for, and the strategies to implement OBP in Korea using MOHO. MOHO is a fast-evolving conceptual practice model whereby often a radical conceptual innovation occurs and a substantial amount of theory refinement with new evidence is generated, and subsequently continuing supports for knowledge dissemination are required. Kielhofner (2005) noted that caution should be applied when considering the traditional scholarship, embedded in the technical rationality, which argues that knowledge generated by scholars will lead to applications of that knowledge. The alternative scholarship, “engaged scholarship,” emphasizes a knowledge-generating system of practice and academic collaboration.

We embarked on our inquiries in the current study on the future adoption of an OBP model based on the call for such a collaboration in the recent 5th edition of the MOHO textbook. The participating national sample of therapists shared their experience and perspectives as follows per the three research questions: First, we found that the rationale for why we need to care about OBP was echoed by the empirical voices of practitioners, with a high level (96.1%) of consensus on the necessity of OBP. When they were asked about the occupational needs they had in mind for their average clients for the six factors influencing participation based on MOHO, therapists reported that they were seeing habituation-related difficulties the most, followed by motor skills issues. Reported difficulties in habituation were regardless of impairment areas, which implies that treatment focus for OBP can be centered on this area for clients as a springboard to further delve into customized treatment planning. In a survey study of a MOHO expert group in the mental health setting in the United Kingdom, the most occupationally challenging area reported was also habituation, followed by volition (Lee et al., 2013). It appears that the current major practice environment in Korea is physical disabilities, which resonated with therapists’ reported experience of seeing the motor skills problem as the second most pressing issue. Although this finding simply shows a general picture of occupational needs among clients seen by participating therapists, the fact that therapists are cognizant of these factors echoes our field’s expertise as role enablers and the accumulated knowledge research base on temporality for a client’s participation in life (Hunt & McKay, 2015; Hwang, Kramer, Cohn, & Barnes, 2020) that can be scrutinized by OBP models.

Second, whether the current supporting system works for preparing practitioners’ competency needed for OBP was not clear from looking at the learning history of participants. We found that practitioners were exposed to a multitude of educational support systems with many variations, using several resources to learn about MOHO. As in the systematic random sample study in the United States, the practitioners indicated a modest usage of MOHO assessments, and familiarity with theories and assessments appears to play an important part in perceiving how to use a theory, as often found in the literature (Crowe & Kanny, 1990; Howe, Sheu, & Hinojosa, 2018). Practitioners who favored Assessment of Motor and Process Skills, the most used MOHO-based assessment in this study, might have been exposed to exemplary rigorous professional development efforts, learning about these assessments in workshops and certificate programs; as noted in the survey, they decided to participate in the survey because such precedent professional development programs were useful. Therapists expressed a desire to use them in their practice more than their current level of adoption, demonstrating readiness and willingness to implement OBP using MOHO, despite the insufficient and questionable resources available to them (e.g., lack of translated assessments, difficult constructs pertaining to therapeutic reasoning process). Taken together, although the number of respondents for this survey is low, it is likely that this cohort is a more motivated group concerning OBP. Though the adoption level of MOHO reported in the current study is not the actual level but the perception of the participants, the desire to use MOHO can be interpreted at face value.

Subsequently, the findings pertaining to the third research question about strategies to implement OBP using MOHO can be taken into consideration to support this motivated group of therapists for the leadership program on MOHO. Multiple strategies were reported as methodologies to enhance the competency-building process. Therapists predicted the most appropriate and anticipated use of MOHO in the community-based OT, school-based OT, and outpatient hospital settings. Because the importance of the interdisciplinary approach in these practice areas is given legislative emphasis nationally and internationally, opportunities to implement OBP with evidence generated by MOHO would be effective and timely. Therapists sought emphasis on customized professional development efforts regarding setting a goal and the therapeutic reasoning process. As a helpful guide, the multifaceted factors identified as important strategies to target included translations of the assessments, educational supports, provision of resources, and actual experience of cases. Notably, the correlation analysis revealed that associations were between the perceived usefulness both of undergraduate and graduate programs and the motivation to use MOHO; use of MOHO and desire to use MOHO; undergraduate experience and graduate experience; and graduate experience and professional experience on some level. This finding implies that a significant amount of commitment and timely dedication would be necessary to apply this satisfying model once it is mastered, which was reported from the experience of the expert group who had used MOHO in the U.K. study. In said study, approximately 1 year of intense professional development efforts was required for mastering the model use. Given that the professional program’s usefulness as found in this study is only modest and inconclusive because of the small sample size, attention should also be paid equally across all levels of the educational support system, maximizing the practitioners’ exposure time to OBP.

As an occupation-focused model, MOHO explains how occupation is motivated (by realizing that we can do things, what is important for us, and what we like), allowing us to take on fulfilling and meaningful roles and organizing our time so that we can live the day/week/life we want. In performance capacity in MOHO, the embodied mind and lived body constructs are incorporated. By achieving occupational competence and overcoming environmental obstacles, we can transform the restrictions and demands we experience into resources and opportunities. A renewed perspective is integrated into one’s narrative, serving as a pivotal momentum to be recognized by practitioners when undertaking the intervention process. As a practitioner’s therapeutic repertoire for OBP expands, entering clients’ lives becomes easier, and the practitioner and client transform together. Practitioners’ concerns and perceived difficulties about this complex process of applying OBP should be treated with respect and care, especially when the most needed resource perceived by therapists was their own will/interests and not the other external supports.

1. Limitations

Although the response rate of this study was acceptable for an online survey, and the probability sampling method had the benefit of methodological rigor, findings were based on the small number of responses available; as such, the results should be treated with caution. In addition, the limitation of the survey study design methodology (i.e., using subjective information instead of objective observation or testing) should be taken into consideration.

2. Implication for occupational therapy

Insights on the strategies to develop curricula and professional development programs found in this study may help support therapists’ path of pursuing OBP. Finding ways to integrate OBP into practice should be undertaken both by academia and practitioners in a partnership effort, wherein a theory-user-attuned education program is established and fortified.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

In this study we described the practitioners’ viewpoint on OBP, empirical needs seen among clients, and perceived strategies to support implementation of OBP through practitioners’ voices. Ongoing development and support for strategies that target and recognize the adult learning process specific to implementing OBP, ameliorating the practice environment for OBP, and transitioning into an individualized learning process is warranted.